What is alcohol?

Alcohol is the common term for ethanol or ethyl alcohol, a chemical substance found in alcoholic beverages such as beer, hard cider, malt liquor, wines, and distilled spirits (liquor). Alcohol is produced by the fermentation of sugars and starches by yeast. Alcohol is also found in some medicines, mouthwashes, and household products (including vanilla extract and other flavorings). This fact sheet focuses on cancer risks associated with the consumption of alcoholic beverages.

According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), a standard alcoholic drink in the United States contains 14.0 grams (0.6 ounces) of pure alcohol. Generally, this amount of pure alcohol is found in:

- 12 ounces of beer (a standard bottle)

- 8–10 ounces of malt liquor (a standard serving size)

- 5 ounces of wine (a typical glass)

- 1.5 ounces of 80-proof liquor or distilled spirits (a "shot")

These amounts are used by public health experts in developing health guidelines about alcohol consumption and to provide a way for people to compare the amounts of alcohol they consume. However, they may not reflect the typical serving sizes people may encounter in daily life.

The federal government’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 does not recommend that individuals who do not drink alcohol start drinking for any reason. The Dietary Guidelines also recommend that people who drink alcohol do so in moderation, by limiting consumption to two drinks or less in a day for men and one drink or less in a day for women, on days when alcohol is consumed.

NIAAA defines heavy alcohol drinking as having four or more drinks on any day or eight or more drinks per week for women and five or more drinks on any day or 15 or more drinks per week for men. Binge drinking is defined as consuming five or more drinks (men), or four or more drinks (women), in about 2 hours. All binge drinking is considered harmful.

A recent Surgeon General’s Advisory has called for reconsidering the recommended limits for alcohol in the US Dietary Guidelines to account for the increased risk of cancer that is associated with consumption of alcohol at or below the guideline levels.

Does alcohol drinking cause cancer?

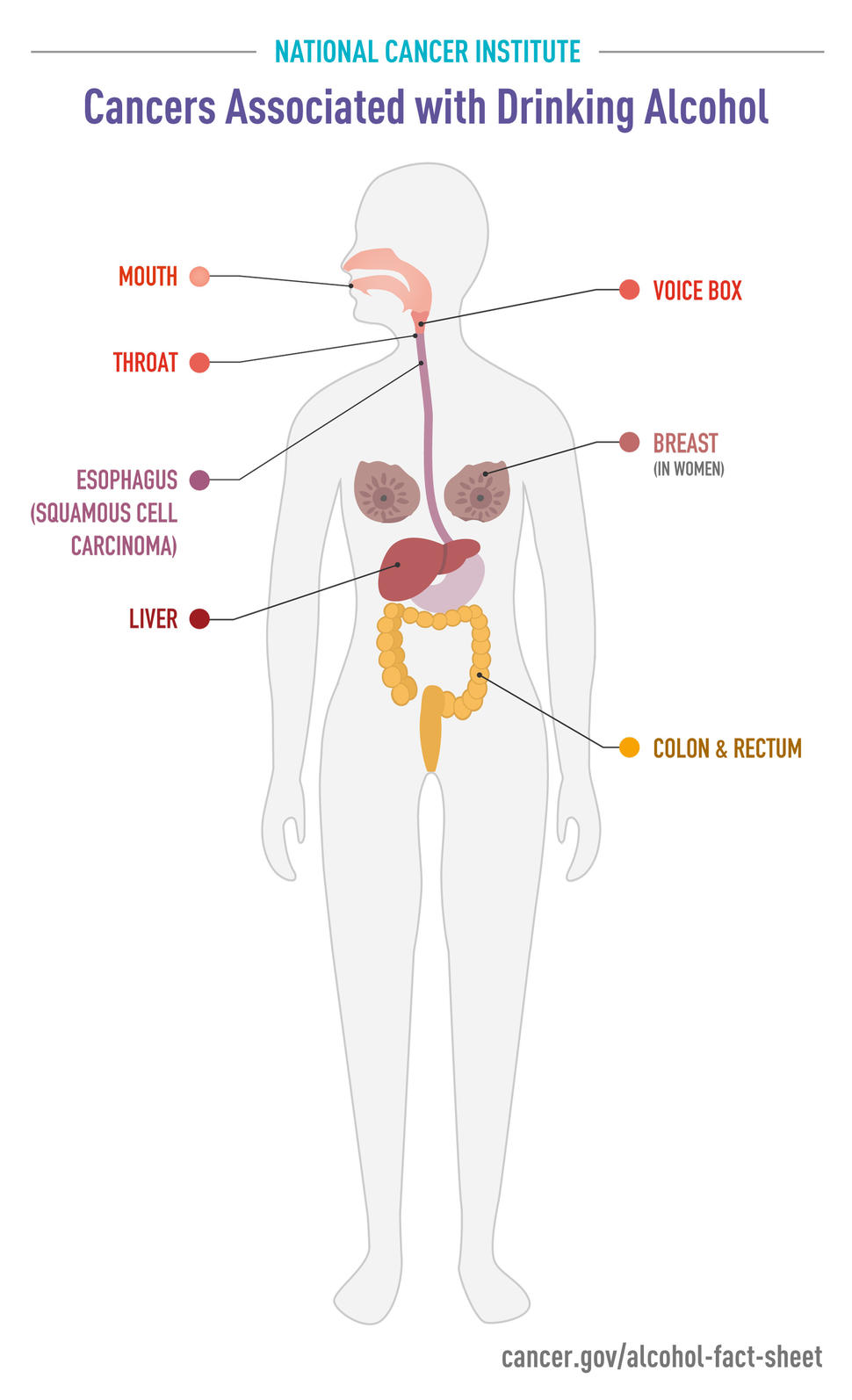

There is strong scientific evidence that alcohol drinking can cause cancer (1, 2). The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified alcohol as a Group 1 carcinogen (cancer-causing substance) in 1987 due to sufficient evidence that it causes cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, and liver in people. The National Toxicology Program has listed consumption of alcoholic beverages as a known human carcinogen in its Report on Carcinogens since the ninth edition, in 2000.

Epidemiologic studies have shown that people who drink alcohol are at higher risk of certain cancers than those who do not drink alcohol and that the more someone drinks, the higher the risk of these cancers. Even light drinkers can be at increased risk of some cancers. For example, women who have just one drink per day have a higher risk of breast cancer than those who have less than one drink a week, and risk is increased even more in heavy drinkers and binge drinkers (3-7).

Alcohol consumption was responsible for about 5%—or nearly 100,000—of the 1.8 million cancer cases diagnosed in the United States in 2019 and about 4%—or nearly 25,000—of the 600,000 US cancer deaths that year (8). Drinking alcohol is associated with increased risks of the following types of cancer compared with not drinking:

| Cancer Type | Risk increases associated with alcohol drinking* | Reference(s) |

| Oral cavity (mouth) and throat | 1.1 times as likely in light drinkers 5 times as likely in heavy drinkers | 4 |

| Voice box | 0.9 times as likely in light drinkers 2.6 times as likely in heavy drinkers | 4 |

| Esophageal (squamous cell carcinoma) | 1.3 times as likely in light drinkers 5 times as likely in heavy drinkers | 4 |

| Liver | 2 times as likely in heavy drinkers | 4, 9, 10 |

| Breast | 1.04 times as likely in light drinkers 1.23 times as likely in moderate drinkers 1.6 times as likely in heavy drinkers | 4, 11, 12 |

| Colorectal | 1.2 to 1.5 times as likely in moderate to heavy drinkers | 4, 11, 13 |

| *Note: these risks are relative risks, which show the proportional chance of a new cancer diagnosis occurring in one group compared with another group (e.g., in those who drink alcohol compared with those who don’t). But it is important to keep in mind that for a less common cancer (such as squamous cell cancer of the esophagus, in the United States), even a large relative risk may represent only a small change in the actual chance that someone will develop that cancer (that is, their absolute risk). By contrast, for a more common cancer, such as breast cancer, even a small relative risk can translate into a large absolute risk. | ||

Using data from Australia, recalculated using US standard drinks, the recent Surgeon General’s Advisory reports that

- among 100 women who have less than one drink per week, about 17 will develop an alcohol-related cancer

- among 100 women who have one drink a day, 19 will develop an alcohol-related cancer

- among 100 women who have two drinks a day, about 22 will develop an alcohol-related cancer

This means that women who have one drink a day have an absolute increase in the risk of an alcohol-related cancer of 2 per 100, and those who have two drinks a day an absolute increase of 5 per 100, compared with those who have less than one drink a week. For men, the number of alcohol-related cancers per 100 is 10 for those who have less than one drink a week, 11 for those who have one drink a day (an increase of 1 per 100), and 13 for those who have two drinks a day (an increase of 3 per 100).

Some evidence suggests that alcohol consumption may also be associated with increased risks of melanoma and of pancreatic, prostate, and stomach cancers (4, 14). However, for cancers of the bladder, ovary, and uterus, either no association with alcohol use has been found or the evidence for an association is inconsistent.

Alcohol consumption has also been associated with decreased risks of kidney cancers (15–17), thyroid cancer (18, 19), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (20–22) in multiple studies. However, the number of cases of these cancers thought to be prevented by alcohol consumption is much lower than the total number of cancer cases attributable to alcohol consumption.

How does alcohol cause cancer?

Researchers have hypothesized multiple ways in which alcohol may increase the risk of cancer (23), including:

- metabolizing (breaking down) ethanol in alcoholic drinks to acetaldehyde, which is a toxic chemical and a probable human carcinogen; acetaldehyde can damage both DNA and proteins

- generating reactive oxygen species (chemically reactive molecules that contain oxygen), which can damage DNA, proteins, and lipids (fats) in the body through a process called oxidation

- impairing the body’s ability to break down and absorb a variety of nutrients that may be associated with decreased cancer risk, including vitamin A; nutrients in the vitamin B complex, such as folate; vitamin C; vitamin D; vitamin E; and carotenoids

- making it easier for the mouth and throat to absorb harmful chemicals, such as those from cigarette smoke, that can lead to cancer

- increasing blood levels of estrogen, which at high levels can cause breast cancer

- negatively influencing one-carbon metabolism and folate absorption, leading to DNA damage (24)

How does the combination of alcohol and tobacco affect cancer risk?

Epidemiologic research shows that people who use both alcohol and tobacco have much greater risks of developing cancers of the oral cavity (mouth), pharynx (throat), larynx, and esophagus than people who use either alcohol or tobacco alone. In fact, for oral and pharyngeal cancers, the harms associated with using both alcohol and tobacco are multiplicative; that is, they are greater than would be expected from adding the individual harms associated with alcohol and tobacco together (25, 26).

Can people's genes affect their risk of alcohol-related cancers?

A person’s risk of alcohol-related cancers is influenced by that person’s genes, specifically the genes that encode enzymes involved in metabolizing (breaking down) alcohol (27).

For example, one way the body metabolizes alcohol is through the activity of an enzyme called alcohol dehydrogenase, or ADH, which converts ethanol into the carcinogenic metabolite acetaldehyde, mainly in the liver. Recent evidence suggests that acetaldehyde production also occurs in the oral cavity and may be influenced by factors such as the oral microbiome (28, 29).

Many individuals of East Asian descent have a "superactive" form of ADH that speeds the conversion of alcohol (ethanol) to toxic acetaldehyde. Among people of Japanese ancestry, those who have this form of ADH have a higher risk of pancreatic cancer than those with the more common form of ADH (30).

Another enzyme, called aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2), metabolizes toxic acetaldehyde to nontoxic substances. Some people, also particularly those of East Asian descent, have a form of this enzyme that causes acetaldehyde to build up when they drink alcohol. The accumulation of acetaldehyde has such unpleasant effects (including facial flushing and heart palpitations) that most people with this ALDH2 variant drink little alcohol and therefore have a low risk of developing alcohol-related cancers.

However, individuals with the altered form of ALDH2 who can tolerate the unpleasant effects of acetaldehyde and consume even moderate amounts of alcohol have a higher risk of alcohol-related esophageal and head and neck cancers than individuals with the normal enzyme who drink similar amounts of alcohol (31, 32). These increased risks are not observed in people who carry the variant but do not drink alcohol.

Can drinking red wine help prevent cancer?

The plant secondary compound resveratrol, found in grapes used to make red wine and some other plants, has been investigated for many possible health effects, including cancer prevention. However, researchers have found no association between moderate consumption of red wine and the risk of developing prostate cancer (33) or colorectal cancer (34). In addition, a recent meta-analysis found no difference between red or white wine consumption and overall cancer risk (35).

What happens to cancer risk after a person stops drinking alcohol?

Studies that have examined whether cancer risk declines after a person stops drinking alcohol have found that stopping alcohol consumption is associated with lower risks of oral cavity and esophageal cancers and possibly of throat, breast, and colorectal cancers (36). It may take years for the risks of cancer to return to those of never drinkers, but it is never too late to stop drinking and reduce the risks.

Is it safe for someone to drink alcohol while undergoing cancer treatment?

As with most questions related to a specific individual’s cancer treatment, it is best for patients to check with their health care team. The doctors and nurses administering the treatment will be able to give specific advice about whether it is safe to consume alcohol while or after undergoing specific cancer treatments. It is important to consider the possibility that alcohol can increase the risk of cancer recurrence or a second cancer.